“In general, I weathered even the worst sermons pretty well. They had the great virtue of causing my mind to wander. Some of the best things I have ever thought of I have thought of during bad sermons. Or I would look out the windows. In winter, when the windows were closed, the church seemed to admit the light strictly on its own terms, as if uneasy about the frank sunshine of this benighted world. In summer, when the sashes were raised, I watched with a great, eager pleasure the town and the fields beyond, the clouds, the trees, the movements of the air—but then the sermons would seem more improbable. I have always loved a window, especially an open one.”1

Wendell Berry is a masterful writer. In one paragraph he captures a wealth of emotions and several insights into the human predicament. It is as if the first-person-speaker represents several church-attendees in a few sentences. First there is the preacher who, despite his best efforts, has delivered a poor sermon. Does he know he is delivering a bad sermon? Can he see it on the faces of the people in the seats; in the eyes that wander or close; in the rustle of pages and shifting of Sunday clothes? Next there is the person whose mind is wandering to other thoughts and other places. What is it that has contributed to these “best things [they] have ever thought?” Is it the preacher; the quiet atmosphere of the church building; or the songs that have been sung? Finally, there is the person who unabashedly stares out the window and observes the creation. Is this person tuned into God or wholly disconnected? Neither the preacher nor the reader knows the answer to these questions. It is as God says in Jeremiah 17:10, “But I, the LORD, search all hearts and examine secret motives. I give all people their due rewards, according to what their actions deserve.” May God be gracious with a greater measure of grace than we have given.

Long Sermon (Brad Paisley)

They’ve read the scripture, they’ve passed the plate

And we’re both prayin’, he don’t preach late

But he’s gettin’ “Amens”, and that’s just our luck

Yeah, it’s eighty-five degrees outside and he’s just gettin’ warmed upOh you and me, we could be soakin’ up that sun

Findin’ out just how fast your brother’s boat’ll run

I tell you there ain’t nothin’ that’ll test your faith

Like a long sermon on a pretty SundayWell it’s been rainin’ all week long

I woke up this mornin’, the dark clouds were gone

We’ve both been raised not to miss church

But on a day like today heaven knows how much it hurts‘Cause you and me, we could be soakin’ up that sun

Findin’ out just how fast your brother’s boat’ll run

I tell you there ain’t nothin’ that’ll test your faith

Like a long sermon on a pretty SundaySee that sunlight shinin’ through that stained glass

How much longer is this gonna lastYeah, you and me, we could be soakin’ up that sun

Findin’ out just how fast your brother’s boat’ll run

I tell you there ain’t nothin’ that’ll test your faith

Like a long sermon on a pretty Sunday

Like a long sermon on a pretty SundayBrad Paisley and Tim Nichols; Published by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, Warner/Chappell Music, Inc.

1. Jayber Crow, Wendel Berry, p.

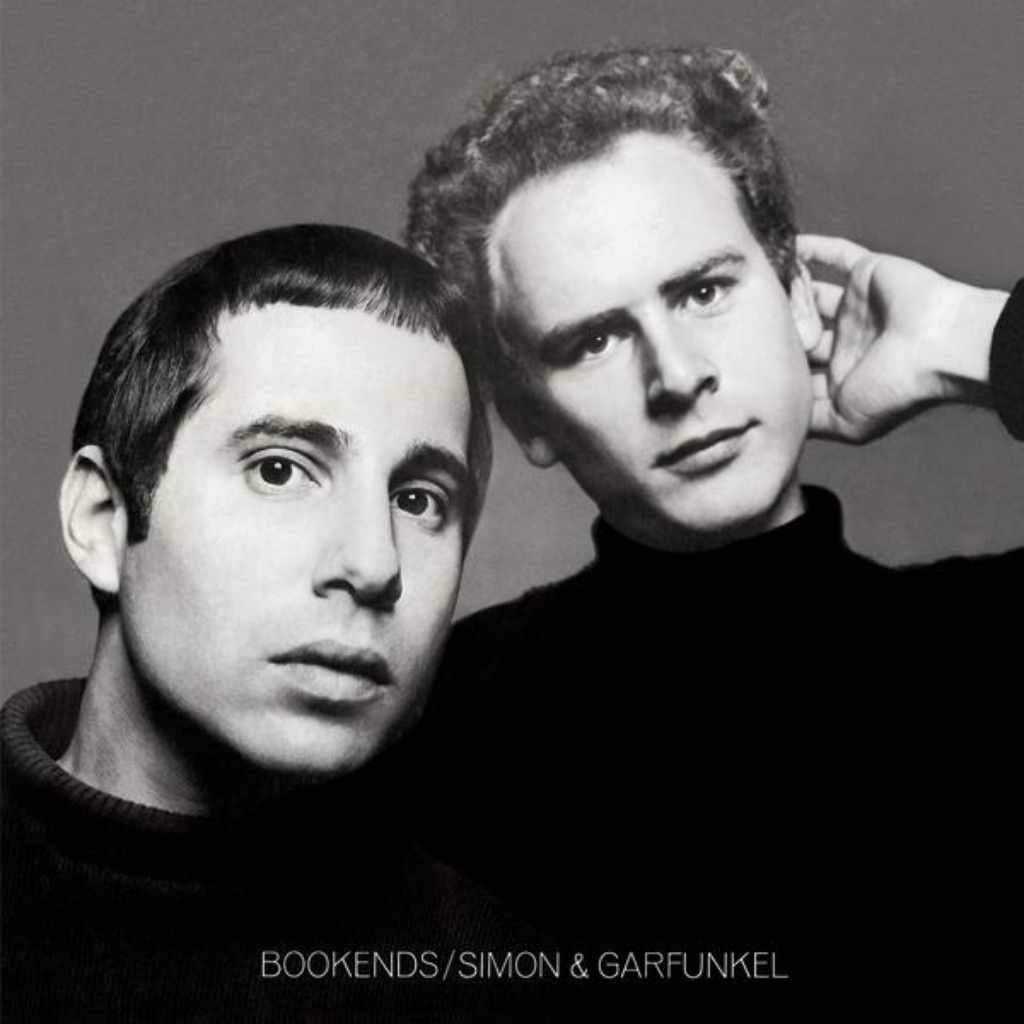

the early sixties and appears on Simon & Garfunkel’s fourth studio album, Bookends (1968). The song is a metaphor

for a life which draws upon the transition from fall to winter. It speaks of a

person who once had great hope, but as time goes on, hope is slowly

transitioning to uncertainty. There is a haze through which the writer cannot

see clearly. He listens to the Salvation Army Band for inspiration but it is unclear

if this gives him any peace. Ultimately, he rejects the message of salvation

and turns back to his vodka and lime while reading his collection of incomplete rhymes. It is a mid-life crisis song in which the singer wonders if he

has accomplished anything in his life and longs for something more; he longs to

be remembered. He recognizes that it should be the springtime of his life, but

the patch of snow on the ground tells him that winter is coming.

Hazy

Shade of Winter

Time,

time time, see what’s become of meWhile

I looked around for my possibilitiesI

was so hard to pleaseBut look aroundThe

leaves are brownAnd

the sky is a hazy shade of winterHear

the Salvation Army bandDown

by the riverside, there’s bound to be a better rideThan

what you’ve got plannedCarry

your cup in your handAnd

look around youLeaves

are brown, nowAnd

the sky is a hazy shade of winterHang

on to your hopes, my friendThat’s

an easy thing to sayBut

if your hopes should pass awaySimply

pretend that you can build them againLook

aroundThe

grass is highThe

fields are ripeIt’s

the springtime of my lifeSeasons

change with the sceneryWeaving

time in a tapestryWon’t

you stop and remember meAt

any convenient time?Funny

how my memory skips while looking over manuscriptsOf

unpublished rhymeDrinking

my vodka and lime

I

look aroundLeaves

are brown, nowAnd

the sky is a hazy shade of winterLook

aroundLeaves

are brownThere’s

a patch of snow on the groundLook

aroundLeaves

are brownThere’s

a patch of snow on the groundLook

aroundLeaves

are brownThere’s

a patch of snow on the groundWords and music written by Paul Simon; published

by Universal Music Publishing Group ©.

The AMC original television series, “Hell on

Wheels,” is the new “Breaking Bad.” Both feature

anti-heroes: men for whom we cheer and hope will survive, at least until the next

episode, even as they leave a trail of death behind them. Both Walter White (“Breaking

Bad”) and Cullen Bohannan (“Hell on Wheels”) are men who have

been broken by tragedy in their past; and because of the tragedy, each becomes

an outlaw and murderer. Both live lives driven by their individual sense of

justice. Of the two of them, Cullen Bohannan is the man with whom we can

empathize and perhaps understand a little more. The horrific death of his wife

and son, at the hands of a renegade troop of Union soldiers during the Civil

War, has left him searching for the evil men who raped and hung his wife. As he

tracks each killer he is confronted by the depravity of the western frontier

where “justice” is meted out by men of power to further their own

interests rather than to achieve a just society.

integrity of Bohannan may indeed be greater than the integrity of those around

him. He achieves a measure of justice by executing those who have tortured and

killed numerous men and women; he feels remorse when he discovers he has killed

a man who was not involved in the slaying of his wife; he is true to his role

as a legally appointed lawman and fulfills his duty in hanging those who

confess to murders; he protects the interests of the poor and oppressed; and he

searches his heart and reforms his character as he becomes a husband and a

father to his new wife and son.

is a model for our own behavior or that he accomplishes his goals in a proper

manner. Bohannan is indeed a fallen man who achieves a level of notoriety and

respect because he seeks to have an integrated sense of justice (individualized

as it is) that keeps him true to what he believes is right. Indeed, in Season

Five, two of the characters will debate whether Bohannan is a loving husband

and father or the devil himself. We await the release of the final episodes to

clarify the verdict, but at least one person has already rendered her judgment

upon this question. In Season Three, Louise Ellison, writer for the Cheyenne

Leader has this to say about the man.

In the

brave new frontier he calls home, integrity is important to Cullen Bohannon.

Whether a man of integrity is what’s needed to build the nation’s first

transcontinental railway, we don’t yet know.The railroad

has always been the business of the unscrupulous and corrupt. I suspect our new

Chief Engineer to be neither, a change of pace from railroad men of the past,

the slick industrialists who made themselves rich at the expense of the U.S.

treasury and the American public.Challenging

times lay ahead, but Cullen Bohannon seems prepared to face them head on. He’s

plagued by a fierce determination, an unbending will to finish this railway no

matter the personal cost. He is a fighter. A survivor. A builder. For that,

dear reader, we might all count our blessings, and say a prayer.1

1. Hell on Wheels Blog Site; http://www.amc.com/shows/hell-on-wheels/talk/2013/08/louise-ellison-column-life-begins-anew-in-u-p-s-hell-on-wheels

A few days ago my thoughts were focused on the fact that we are all “terminal.” Today my mind turns to the things within us that drive us to keep on living. We have likely all known someone who planned to “live a hard life, have a good time, and die young” only to be surprised when they managed to achieve some measure of greater age and found that they did not want to die. Agatha Christie once said,

“I like living. I have sometimes been wildly despairing, acutely miserable, racked with sorrow, but through it all I still know quite certainly that just to be alive is a grand thing.”

Similarly, Dylan Thomas wrote,

“Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

There is certainly something within that keeps us striving to live at almost any cost; and I would not want to discourage anyone from choosing to stay alive. Perhaps the best we can do is determine to know that we are indeed dying a little every day; and then, also know that every moment we have on this earth counts for something. We can choose how we will live these days we have on earth. There are many who choose to live each one in pursuit of personal gain. There are also many who choose to help others achieve a measure of success. Still another group seeks to “Love the Lord [their] God with all [their] heart, soul, strength, and mind and love [their] neighbour” as themselves. (Luke 10:27) The question I must ask myself is, “How will I live and die upon this earth?”

“Death is to be warded off by exercise, by healthy

habits, by medical advances. What cannot be halted can be delayed, and what

cannot forever be delayed can be denied. But all our progress and all our

protest notwithstanding, the mortality rate holds steady at 100 percent.”[1]

where it is more and more common to have no funeral or memorial service, we

still cannot hide the fact that death is inevitable. I have had friends that

died at 58, I have friends that are alive at 96. We all know that one day we

must leave this place. We await the mystery of death.

an essay which was published in February of 2000. In this essay he considers

his attitude toward death after nearly dying in 1993. It is a marvelous essay and I encourage you to read it here.

large tumor that had ruptured his colon, the surgeon told Neuhaus, “It was as

though you had been hit twice by a Mack truck going sixty miles an hour. I

didn’t think you’d survive.” As he began to recover and regain enough strength

to walk around the block, he recounts some of his feelings as he realized we

are all “born toward dying.”

“Shuffling around the block and then, later, around several

blocks, I was tired of [New York]. Death was everywhere. The children at the

playground at 19th Street and Second Avenue I saw as corpses covered with

putrefying skin. The bright young model prancing up Park Avenue with her

portfolio under her arm and dreaming of the success she is to be, doesn’t she

know she’s going to die, that she’s already dying? I wanted to cry out to

everybody and everything, “Don’t you know what’s happening?” But I didn’t. Let

them be in their innocence and ignorance.”

we struggle against it, but we are all dying.

flawed and we must not “let our spirit die before our body does.”

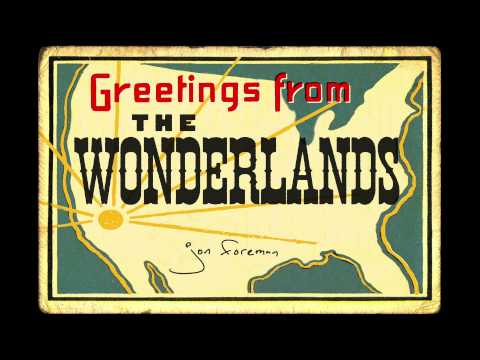

Terminal(words and music by Jon Foreman)The doctor says I’m dying

I die a little every day

He’s got no prescription

That could take my death away

The doctor says, “It don’t look so good”

It’s terminalSome folks die in offices

One day at a time

They could live a hundred years

But their soul’s already died

Don’t let your spirit die before your body does

We’re terminal, we’re terminal, we’re terminalWe are, we are the living souls

With terminal hearts, terminal parts

Flickering like candles, shimmering like candles

We’re fatally flawed, fatally flawedWhenever I start cursing

At the traffic or the phone

I remind myself that we have all got

Cancer in our bones

Don’t yell at the dead

Show a little respect

It’s terminal, it’s terminalWe are, we are the living souls

With terminal hearts, terminal parts

Flickering like candles, flickering like candles

We’re fatally flawed, we’re fatally flawedWe are, we are the living souls

With terminal hearts, terminal parts

Flickering like candles, flickering like candles

We’re fatally flawed, we’re fatally flawed“Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust

For our days here are like grass

We flourish like a flower of the field

The wind blows and it is gone

And its place remembers it no more

Naked we came from our mother’s womb

And naked we will depart

For we bring nothing into the world

And we can take nothing away”We are, we are, we are, we are, we are the living souls

With terminal hearts, terminal parts

Flickering like candles, flickering like candles

We’re fatally flawed, in the image of God.

terminal. I hope that doesn’t come as a shock to you. Some of us have been

fortunate to live many good years on this earth. We know all too many who have

died before their time. But, what is before their time? What is before my time?

Does anyone know how many days he or she has been given on this earth? “Our days on

earth are like grass; like wildflowers, we bloom and die. The wind blows, and

we are gone – as though we had never been here” (Psalm 103:15, 16). Oh, God, “Teach

us to number our days, that we may gain a heart of wisdom” (Psalm 90:12) for we

are fatally flawed, in the image of God. We’re terminal.

2000, http://www.firstthings.com/article/2000/02/born-toward-dying

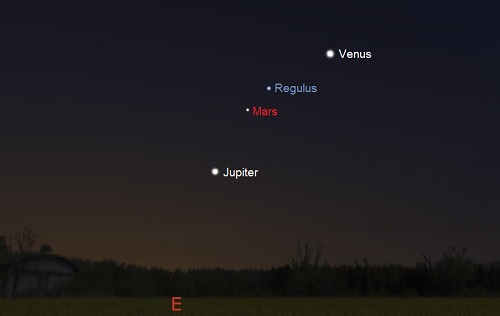

Starship 21ZNA9A good friend of mineStudies the starsVenus and MarsAre alright tonight"Venus and Mars" lyrics by Paul McCartney and Linda McCartney; published by MPL Communications, Inc.

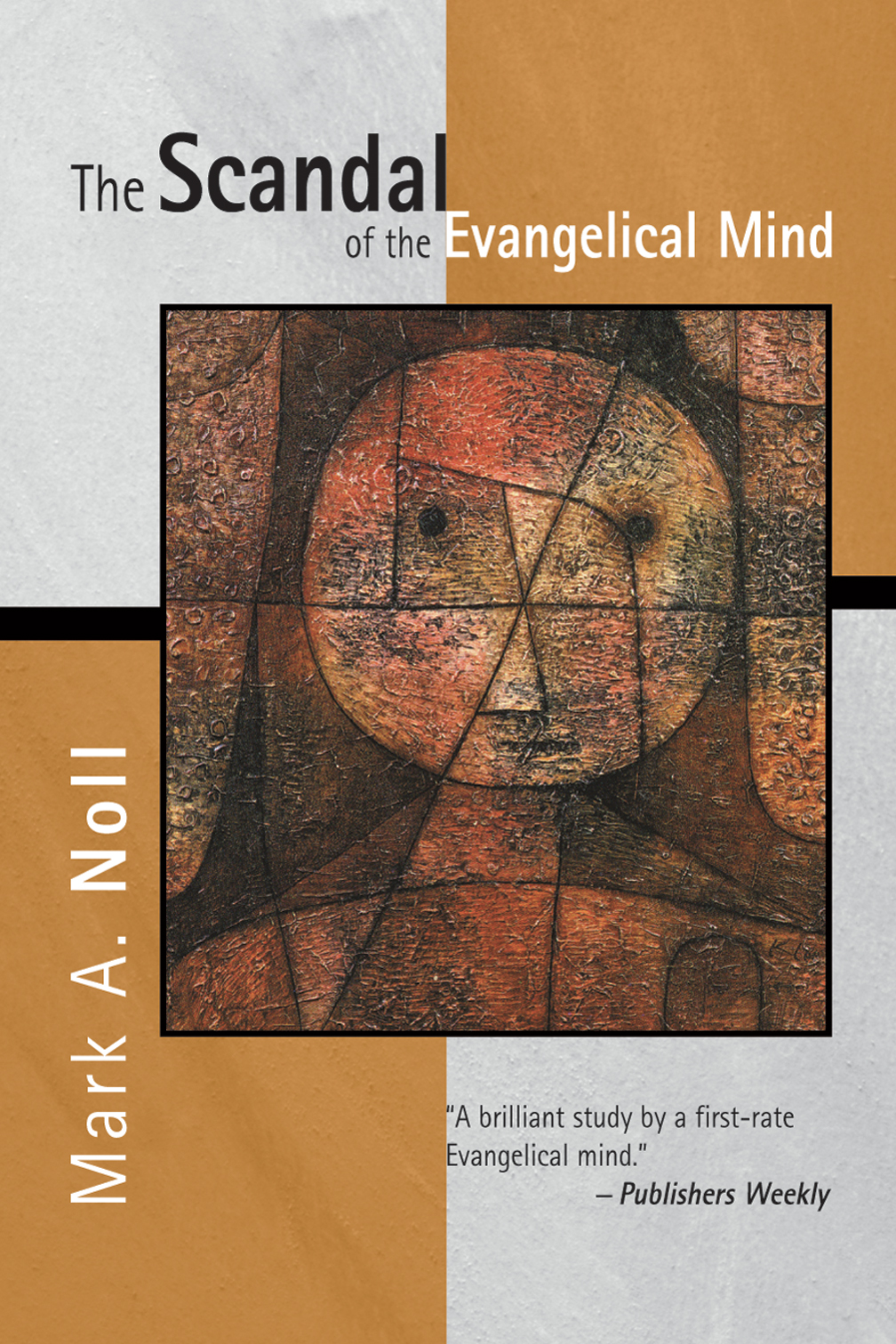

I have never met Mark A. Noll; but, if we

ever do have a conversation together, I expect I would find myself very much

agreeing with him. He is the sort of intellectual writer who is unafraid to

turn over all of the stones and search for every seed of truth. He desires to take

each gem of enlightenment captive to Christ. His most widely read book, The

Scandal of the Evangelical Mind,

contains many great insights on the way in which mainstream Evangelicalism

strayed so far from truth. He says,

the supernatural, fundamentalists and their evangelical heirs resemble some

cancer patients. In facing a drastic disease, they are willing to undertake a

drastic remedy. The treatment of fundamentalism may be said to have succeeded;

the patient survived. But at least for the life of the mind, what survived was

a patient horribly disfigured by the cure itself.[1]

loss of a critical mind that exhibits a measure of skepticism regarding the

miraculous and a healthy measure of skepticism appropriate to the scientific

method. He is desirous that all Christians might live within the tension of

belief and uncertainty. He further explains. “I was brought

up in a Christian environment where, because God had to be given pre-eminence,

nothing else was allowed to be important. I have broken through to the position

that because God exists, everything has significance.”[2]

provides the raw material for physical sciences)? Who formed the universe of

human interactions (which is the raw material of politics, economics,

sociology, and history)? Who is the source of all harmony, form, and narrative

pattern (which is the raw material for art)? Who is the source of the human

mind (which is the raw material for philosophy and psychology)? And who, moment

by moment, maintains the connection between our minds and the world beyond our

minds? God did, and God does.[3]

each consider the relationship between faith and science, belief and

agnosticism, and spirituality and materialism. May those who have comprehending

minds meditate upon these thoughts.

Works Cited

Evangelical Mind. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1995.

[3] (Noll 1995)

In his brilliant novel, Jayber Crow, Wendell Berry creates a particular scene to illustrate a point. Jayber Crow, who is

narrating his own story, is the town barber and, as is the lot of a small-town

barber, hears many conversations in his barber shop. Some of these

conversations are entertaining, amusing, and educational. Others are just plain

ignorant. He recounts the following interaction with Troy Chatham.

evening, while Troy was waiting his turn in the chair, the subject was started

and Troy said – it was about the third thing said – “They ought to round up

every one of them sons of bitches and put them right in front of the damned

communists, and then whoever killed who, it would be all to the good.”

little pause after that. Nobody wanted to try to top it. . . .

do, but I quit cutting hair and looked at Troy. I said, “Love your enemies,

bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you.”

head up and widened his eyes at me. “Where did you get that crap?”

Christ.”

“Oh.”

been a great moment in the history of Christianity, except that I did not love

Troy.[1]

easy it is to love our enemies in the abstract. It is difficult to love actual

people.

Works Cited

Crow. Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2000.

2000, 287)

Anyone

who has read this blog for any length of time will know that I rely heavily

upon the writings and sayings of others. I frequently use the words that

another has said or written as a jumping off point for exploring my own

thoughts. Most of the time, I am confident that this is a fruitful method. Yet,

I am also aware of the pitfalls of such an approach and have often witnessed

problems with this technique in the writings of others; and so I know that it

must also exist in mine. The basic difficulty lies in the fact that by taking

one small snippet of a writer’s thoughts, we run the risk of missing their

meaning and perhaps interpreting their words in the opposite sense in which

they were intended. For example, if one searches for quotes written by Wendell

Berry in his book, Jayber Crow, you

will find, online, a preponderance of quotes which support pessimism toward God

or toward his existence. Here is an example of an often used quote that, at

first glance, suggests that Berry is a proponent of atheism:

said, “if Jesus said for us to love our enemies – and He did say that,

didn’t He? – how can it ever be right to kill our enemies? And if

He said not to pray in public, how come we’re all the time praying in

public? And if Jesus’ own prayer in the garden wasn’t granted, what is

there for us to pray, except ‘thy will be done,’ which there’s no use praying

because it will be done anyhow?” . . . He said, “Have you any

more?”

said, for it had just occurred to me, “suppose you prayed for something

and you got it, how do you know how you got it? How do you know

you didn’t get it because you were going to get it whether you prayed for it or

not? So how do you know it does any good to pray? You would need

proof, wouldn’t you?”

proof.”

each other.

answers?”

cannot be given answers. You will have to live them out – perhaps a

little at a time.”

take?”

you live, perhaps.”

time.”

mystery,” he said. “It may take longer.”[1]

questions Wendell Berry’s character, Jayber Crow, asks are typical of one who

has had faith and then lost it. They suggest someone who is trying hard to

believe in Jesus, but just can’t do it. For those who like to draw quotes from

Wendell Berry to suggest agnosticism, this is sufficient to prove their point that, it is not rational to believe in a God who answers prayer and interacts

with His creation.

Crow says these words at a point that is one sixth of the way through the book.

One has to go a full two-thirds of the way through the book to see the answer

Jayber Crow gives himself. The answer, which shows a renewed faith in Jesus,

goes like this:

knew… why Christ’s prayer in the garden could not be granted. He had been

seeded and birthed into human flesh. He was one of us. Once He had become mortal,

He could not become immortal except by dying. That He prayed the prayer at all

showed how human He was. That He knew it could not be granted showed his

divinity; that He prayed it anyhow showed His mortality, His mortal love of

life that His death made immortal. . . .

the world, might that not be proved in my own love for it? I prayed to know in

my heart His love for the world, and this was my most prideful, foolish, and

dangerous prayer. It was my step into the abyss. As soon as I prayed it, I knew

that I would die. I knew the old wrong and the death that lay in the world.

Just as a good man would not coerce the love of his wife, God does not coerce

the love of His human creatures, not for Himself or for the world or for

another. To allow that love to exist fully and freely, He must allow it not to

exist at all. His love is suffering. It is our freedom and His sorrow. To love

the world as much even as I could love it would be suffering also, for I would

fail. And yet all the good I know is in this, that a man might so love this

world that it would break his heart.”[2]

are the words of a man who has found a renewal of his faith. These are the

words of someone who will trust Jesus. The point is, one must consider the

whole body of work before concluding the position of the author on this

particular issue. One small, or large, quote does not fully represent the

beliefs of Jayber Crow or, by extension, the beliefs of Wendell Berry. The

bottom line, for both writers and readers, is that we must not be lazy about

investigating the thoughts of an author. Truly substantiating a point may

require a good deal more reading than most of us choose to invest. Becoming

true scholars, knowledgeable readers, and connoisseurs of words will require a

good deal more outlay of time; but, as good scholars will know, the investment

is worth the reward.