strongest impulses within most of us is the belief that good people are rewarded,

and bad people are punished. There is an immediacy to it. When bad things begin

to happen to us, we quickly ask, “What did I ever do to deserve this?” When

someone else is suffering in life, there is a natural tendency to see them as

getting what they deserve. We love stories of “good people” who win the

lottery. We like to believe it is because they deserve it. As a pastor and leader in the church, people often come to

me for counsel and many times they speak of a feeling that they are being

punished for wrong they have done. Even Jesus’ own disciples assume this “retribution

theology” when they ask Jesus about their encounter with a blind man. “Who

sinned, this man or his parents that he has been born blind,” they ask (John

9:2).[1]

Jesus immediately corrects them and says neither, and yet you and I still tend

to think that this is the way the world works. Proponents of the Prosperity

Gospel use our natural tendency and try to convince us that this is indeed the

way the world works.[2]

Job in the Old Testament is designed to help us understand the true way God

functions. The preface of the book of Job is where we must begin and be certain

to understand that Job is considered by God himself to be “innocent and

virtuous” (1:8; and 2:3) long before and even after the calamities come upon

him. The Accuser believes that if Job lost all that he had, and if his health

was taken away, he would no longer be innocent, virtuous, and faithful to God.

But God allows the Accuser to take away all of the good in Job’s life and still

Job remains faithful, virtuous, and innocent.

the book is an explanation of the common understanding of retribution theology

which Job’s friends and even Job seem to endorse. There is this sense in which

humans are forever believing that if someone is suffering, they must have

sinned; and even when the evidence suggests otherwise, we will continue to believe

in this retribution theology.

reading this article will argue that, indeed, retribution theology is the way

in which God functions. They would show proof-texts from the book of Proverbs,

or Deuteronomy 27, 28 (which connects obedience to God’s law with rewards and

disobedience with curses) and tell us that is precisely how God functions.

However, Tremper Longman III explains it this way.

the book of Job…is to undermine the idea that retribution theology works

absolutely and mechanically. Sometimes sin does lead to negative consequences,

but not always. Similarly, sometimes proper behavior leads to positive

outcomes, but not always. Job serves as an example to warn against judging

others on the basis of their situation in life.” (p. 67).

fully answers why Job suffers. God simply appears before Job and it is clear to

Job that God is the only wise one. Job “repents” at the sight of an

all-powerful God. But his repentance is not from

dialogues, Job has grown increasingly impatient… He concludes that God is

unjust. At the end of the story, he changes his attitude and behavior (he

repents, in other words) toward God, now that he has not only heard about him

but also seen him (42:5).”[3]

the Book of Job is that, regarding suffering, “…the ultimate resolution is

patient suffering before a wise and powerful God.”[4] We

may not understand it ourselves, but we can trust the wisdom of our God as we

go through the sufferings of this life. Job is an important book that teaches

about wisdom and suffering. May we read it carefully and mine all of the truths

it has to offer.

Here and throughout this article, I rely heavily upon Tremper Longman III’s

excellent commentary on the book of Job and particularly the essay contained

within it entitled “The Theological Message of the Book of Job.” Job (Baker Commentary on the Old Testament

Wisdom and Psalms), Baker Academic, 2012 Commentary by Tremper Longman III.

Longman p. 65, 66.

Longman p. 68.

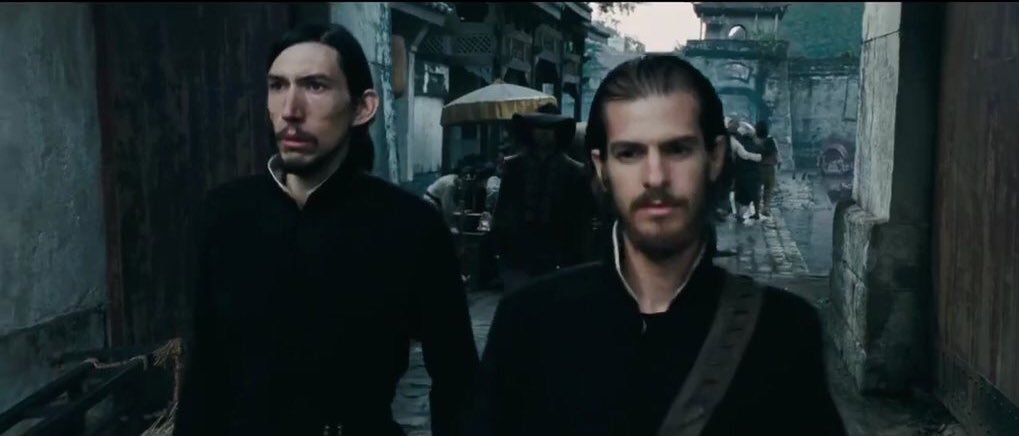

die for the good and beautiful. It is easy enough to die for the good and

beautiful; the hard thing is to die for the miserable and corrupt.”

-Shusaku Endo; Silence,

Picador, 2016.

Snow)

Angel Snow)

dancin’ ’round inside my head

I’m tryin’ not to lose everything she said

Even so in standing at the foot of my bed last night

This mountains gettin’ higher with every step

I’m trying not to lose everything I’ve kept

Captured by the fortune tellers in my mind

Ooohh, they always come back again

Every time freedom tries to pull me out

They suck me back in

Oooohh, we gonna’ let that fire burn you

Tell me how you’re gonna’ walk on coals and water too

Can you taste these words fallin’ from my mouth

“Ain’t old fashioned love what it’s all about?”

I heard an old black man shout Christmas eve

Should’ve known better than to run to you

My heart started talking to me way to soon

Damn those fortune tellers in my mind

Oooohh, they always come back again

Every time freedom tries to pull me out

They suck me back in

Oooohh, we gonna’ let that fire burn you

Tell me how your gonna’ walk on coals and water too

walk on coals and water too

and a scripture speaking of roads. Each item is about making choices. The song

by Krauss and Snow is about the mistakes in life and the roads taken that were

wrong choices that affect the rest of our lives – and about the resolve to not

make the same or even worse mistakes again. Taking the “road less traveled

on” is seen as the way to avoid such mistakes.

Frost seems to choose (although there is some discussion about exactly which

road the person chooses) the path that is less worn, the path that fewer people

take. Jesus calls us to take the narrow road that is taken by fewer people. The

question for us is, “what is the path less travelled?” How do we know whether

or not we are on that path? Certainly, the path of following Jesus is a path

less travelled. But, even then, there is a tendency to follow the crowd who

seem to be following Jesus rather than to truly keep our eyes on the Master.

sigh is truly the key to understanding the thoughts of this poet and the

meaning of the poem (not necessarily one and the same). Certainly, to

understand each of these poetic stories, one must take into account longing and

regret, right and wrong, good choices and poor choices. Jesus calls us to the

narrow way that few travel; but I must guard my own heart and mind so that I

might not think too highly of the path I have chosen for myself. What of

further branching of the road? I may have made one right or wrong choice but, in the immortal words of Robert Plant,

But in the long run

There’s still time to change the road you’re on.” (lyrics to “Stairway to Heaven”)

topic. Discussion will follow in the next few days. For now, ponder the words

of a song by Viktor Krauss (Alison’s brother) and Angel Snow, a poem by Robert

Frost, and the words of Jesus Christ in the Gospel of Matthew. Note well how

each of these phrases is used: “this road less traveled,” “two roads diverged,”

“the other” road, the road “less traveled by,” “narrow gate,” “highway to hell,”

and “gateway to life.”

Days

slow

a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Living Translation (NLT)

Kingdom only through the narrow gate. The highway to hell is broad, and

its gate is wide for the many who choose that way. But the gateway to life

is very narrow and the road is difficult, and only a few ever find it.”

“What we are looking for in reading the Bible is the ability to turn the

two-dimensional words on paper into a three-dimensional encounter with God, so

that the text takes on life and meaning and depth and perspective and gives us

direction for what to do today.” ― Scot McKnight[1]

we follow the Bible or do we follow Jesus?” “Are Christians lovers of the book

or lovers of the Lord?” These can be challenging questions for many of us. Perhaps

McKnight gets closest to the answer by reminding us that the words we read in

our Bible are a simplified (2-D) representation of a complex life (3-D).

Whether we are reading about Jesus or Noah, the words on the page will never

fully represent the intricacies of a life lived with temptations, triumph, and

tears. May our hearts reverently approach the word of God with awe and humility,

seeking always the truth behind text on a page.

Read the Bible, Zondervan, 2016.

In Romans

9:3, Paul the Apostle expresses the emotion that, “for my people, my

Jewish brothers and sisters. I would be willing to be forever cursed—cut

off from Christ!—if that would save them.” A great many commentators and

writers have attempted to understand just what Paul meant by these words. We do

well to note the conditional nature of the phrase. We get the impression that

Paul knows that what he is saying is not the way God works. Paul cannot make a

bargain with God whereby Paul is forever cut off from Christ to save the Jewish

people. Salvation is more complex than such a scenario implies and Saint Paul

is well-aware that he cannot save the Jewish people in such a way.

remainder of this blog contains spoilers

for the movie, Silence, 2016 and the

blog will make more sense after you watch the movie.) Martin Scorsese also

understands that salvation, damnation, faith, suffering, pride, and apostasy

are more complex than we may be led to believe and has created a movie that

opens up a conversation regarding these concepts. At two hours forty-one

minutes in length, it is long and sometimes grueling to watch. It requires substantial

concentration to catch the nuances that are significant to the plot of the

movie: the triumphant faces of two Catholic Missionaries setting off for fame,

martyrdom, and glory as they imagine their fate as heroes of the faith; an

expression on a face that betrays inner doubts or tremendous pride; a rooster

crowing in the distance following a particularly eventful rejection of Christ.

scenes of Christians being tortured for their faith. The movie is set in Japan in the

early 1600’s when Christianity was suppressed by fierce war-lords or shoguns.

The first missionaries to Japan (Portuguese Jesuits) were well-received and

many Japanese became followers of Jesus and members of the Catholic Church. However,

many of these new converts were given Portuguese Christian names and encouraged

to adopt Western culture which caused the local authorities to look upon

Christianity as a subversion of Japanese culture and a threat to their way of

life. Persecutions and pressures to renounce the faith soon followed.[1]

seek to understand God in the midst of horrific persecution. The title refers

to the quiet with which God responds to their prayers. They pray for rescue,

relief from torture, strength to keep their faith, and the growth of the Gospel

in Japan – and Jesus is silent to them. When Jesus does finally respond, his

voice is unexpected and contradictory to the proclamation we anticipated.

movie upon the 1966 book (English translation 1969) by Shusaku Endo and has spoken of making the movie as

“a pilgrimage” back into his Catholic faith. In interviews about the movie, he

identifies pride as one of the key themes of the movie. In the discussion of

pride and going to extreme measures to save others, we are led back to the

first words of this blog in which we discussed Saint Paul’s words to the Romans

(more on that in a moment).

most difficult questions of the movie. What is it that motivates the priests to

travel to Japan and preach the Gospel? They are aware that it means certain torture and death, yet they go anyway. Is it truly because of a love for the

people of Japan or pride in being the ones to carry the Gospel and die for

their faith? The priests are not afraid to die for their faith, but what they

were not prepared for was the fact that others would be tortured and killed

before their eyes as a way to make them recant their own faith. One priest

(Ferreira), who has already renounced his faith, demands that Rodrigues

renounce his as well to save those who are being tortured until Rodrigues apostatizes.

Another Christian readily renounces his faith, confesses, and takes up the

faith again, over and over. What should a Christian do? What should a faithful

missionary do?

first interview with Rodrigues, identifies that Rodrigues is filled with pride and arrogance. He perceives pride in the Portuguese

culture that maintains its superiority and looks down on the inferior Japanese.

He is aware of the colonialism that is brought with the Gospel and a lack of

understanding that Japanese culture has anything to offer. Rodrigues’ own words

written to his superiors in Portugal belie his pride as he recounts the joy

he felt in baptizing hundreds of Japanese Christians.

come full-circle to the initial scripture passage to which I referred. The Apostle Paul recognized his own pride as he wrestled with how he might save

the Jewish people. Just in time, he comes to realize that his sacrifice will

not save the Jewish people. It is only in Christ that salvation can be found.

We must leave the mystery of salvation to Jesus. He is the one who must work in

the hearts of others. We are responsible for our actions, our thoughts, and our

submission to Christ. Even our own pride in carrying the Gospel of Jesus Christ

is pride just the same. Our joy in doing God’s work can easily fall into pride

in ourselves. How many times have I done the right thing (even caring for the

poor or baptizing those who confess Christ) and my joy turns to pride and sours

the very work I have done? I give a few coins to the poor and find myself

telling others about this thing I have done – when I ought to be “silent!”

reflecting on this movie, asks the difficult question, “Is unwavering

commitment to one’s understanding of absolute truth itself a form of arrogance

and spiritual pride?”[2] The world in which we live is complex and how God is

involved in salvation of the cosmos is mysterious. Pride is believing that we

have all of the answers for every culture, every circumstance, and every

person. I must not commit myself to “my understanding of absolute truth.” My

commitment must always be to “seeking the truth.” What can I learn from

Canadian culture in all of its forms? What do I learn from Japanese culture?

American culture (yes, even culture which seems alien and people who espouse

ideas with which I disagree)? How do we live lives that are truly reliant upon

Jesus and not be prideful when we achieve some degree of reliance upon Him?

end up living as hidden Christians who study the Japanese culture and appear to

be living as Japanese Buddhists. In fact, their Christian faith (one wonders if

it exists at all) is supplanted so far below the surface that all will see them

as Japanese Buddhists. Ferreira begins to believe that Portuguese culture might

actually have something to offer Japan, but it is in astronomy and not

Christianity that he believes Portugal has the most to offer.

and perhaps I will come back to it again.

Scorsese admits to being a lapsed Catholic and yet, I believe God has given him a voice to ask difficult questions and help us to understand

ourselves more deeply. May God give us the grace to live humble lives while

speaking boldly for Jesus Christ.

Many are asking the question, “Do faith and science conflict?” and many would say they know the answer. In this message delivered at Bow Valley Christian Church on January 7, 2018, I offer the answer of one who has worked in and studied the sciences while also living and studying a life of faith. I pray that it might be a helpful voice in the midst of much confusion. To hear this message, select the links embedded in the text.

by Michael Gracey; written by Jenny Bicks and Bill Condon)

contained in this film, see the movie before reading this blog.)

read this blog will not be surprised to hear that I enjoyed another musical.

The Greatest Showman is top-notch

musical entertainment and leaves one with things to consider. The whole time I

watched the show I felt drawn to finding a community theatre company in which I

could sing and act. I wanted to be Hugh Jackman as much as he wanted to be P.T.

Barnum. As I left the theatre I was reminded of the realities of life that would

get in the way of such aspirations, but I suspect that musicals like this do

inspire others to act, sing, dance, write stories, and compose music. Such

movies are good for our collective consciousness.

invented “showbiz.” The theme that is perhaps most prevalent is the idea that

every life matters and that our differences should be celebrated. I found that

the actors, director, and producers did well to make this an important theme

without clobbering the audience with the concept. Yes, there are moments when Lettie Lutz (the bearded lady) is overpowering with the message of celebrating differences;

but there are also times when we see that P.T. Barnum and others who revered diversity

were flawed and simply enjoyed a good “freak show.” The film is accurate in

recognizing the struggle we all face in embracing those who are exceptional.

also contemplates questions about status and station in life. Barnum is shown

to have been born into poverty and low social-standing and he is always on a

search to achieve a greater status. He is never satisfied with money or fame as

long as he is treated as a lesser citizen. Never is this clearer than in his

interactions with his wife’s parents and their high-society friends.

naturally leads to introspection about the question of “when is enough, enough?”

Capitalism, and the search for a good life with sufficient wealth is seen to be

in conflict with diversity, status, and satisfying relationships. Of course,

these questions also affect two significant love stories held within the movie.

Barnum’s quest for status, fame, and money get in the way of his relationship

with his children and his wife, Charity. Meanwhile, Phillip Carlyle, who comes

from a wealthy family of high social-standing finds it hard to leave behind the

adoration of high-society to fully embrace his love for Anne Wheeler, a common

trapeze artist in the circus.

singing, dancing, lyrics, special effects, and colours of the movie are all

well-done. I encourage you to see it for yourself and let me know your reactions.

2, Episode 6: Vergangenheit

Peter Morgan

Philippa Lowthorpe

contains numerous spoilers and explanations of a current episode of The Crown. You may want to watch the

episode before reading this article.

word, vergangenheit, has many uses [1]

in the German language. Its simplest meaning is “the past.” In some contexts,

this can be a “time that has elapsed,” a “forgotten past,” a “past with which

some have not yet come to terms,” or a “past that needs to be forgiven.” This

is the word the producers and writers chose for Season 2, Episode 6 of the

Netflix series, The Crown.

opens with the uncovering of secret Nazi documents which reveal the plans and

thought processes of the senior Nazi leadership and their collusion with

European leaders prior to and during World War II. Most of the documents are

translated and published, while the Marburg papers are labelled confidential

and stored away in secret so that the embarrassing contents might never be

revealed.

quickly shifts to King George, who, on discovering the contents of the Marburg

papers, says that the people of the world must never discover the contents. He

says, “Our people would rightfully never forgive us.”

most will see the story as a depiction of what to do with a former King (Edward VIII) who

wants to rehabilitate his image, the interesting part of this British drama is

the question of “forgiveness.” If one notices how many times the word is used

in this script, they will get the sense that the discussions between the Head

of the Church of England (Queen Elizabeth II) and the unofficial Head of

Evangelical Christianity in America (Reverend Billy Graham) are much more than

peripheral to the overall development of the episode.

we cannot get away from the fact that Her Majesty is wrestling with how to, and

whether or not to, forgive her uncle, the former King Edward VIII (and

subsequently the Duke of Windsor), for associating and conspiring with Nazi

Germany in a failed attempt to recover the throne for himself and his wife who

wished to be Queen. In this version of historical-fiction, the Duke of Windsor

is seen as one who wanted the throne but could not have it because of the

divorced woman he chose to marry. Yet, the question of forgiveness is bigger

than one act of pardon or denunciation. Forgiveness here, in the context of this well-written and well-directed program, is about forgiveness in all its forms.

God forgiving individuals.

for the individual, hope for society, hope for the world.”

forgiving Kings.

forgiving a German political movement which brought about the Nazi Party and

the horrors of World War II. At one point, we hear the Duke of Windsor suggest

that, “It could be argued that we were the ones that made him [Hitler] a

monster.”

forgiving oneself.

forgiveness for oneself … and prays for those whom one cannot forgive.”

is played out with commentary provided by the private words spoken between The

Reverend Billy Graham and Her Majesty, The Queen. Graham preaches a question

and then answers it for the small audience in Windsor Chapel.

it means, that you have a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.” (Here he

references Colossians 1:27.)

praises Billy Graham, the evangelist, and says, “You speak with such clarity

and certainty.… It is lovely to disappear and become just a simple Christian.” By

that, she means that it felt good to be in chapel and not feel that she had to be the

Head of the Church.

shift back and forth but we are soon taken to a scene featuring the Duke of

Windsor as he writes to his wife in America. He complains that the evangelist, Billy

Graham, has disturbed him and says that “all taste for prayer has evaded me.”

We begin to see the Duke transformed from a bored socialite to a demon in

disguise. One scene ends with a fade to black in which a menacing glint in his

eyes is the last thing to fade. When the publication of the Marburg papers

becomes inevitable, the Queen Mother remarks that “this was always going to

come back to haunt us.”

Queen and The Evangelist are eager to want to forgive The Duke and the sins of

others, even as they admit to the difficulty of forgiving those who betray and

murder their countrymen. At one point the Queen says, “It is time to discuss forgiveness

for Uncle David. … Forgiveness is very important to me.” However, when she is

confronted with the magnitude of David’s sins, perhaps there is even an

allusion here to King David of the Bible, she speaks these harsher words to her

uncle,

when the truth finally came out, it makes a mockery of even the central tenants

of Christianity. There is no possibility of my forgiving you; the question is,

how on earth can you forgive yourself?”

this point that the key conversation between Billy Graham and The Queen occurs.

circumstances in which one can be a good Christian and not forgive?”

asks for forgiveness for oneself … and prays for those whom one cannot forgive.”

refreshing to see a historical-fiction from the UK tell a redeeming story of the

power of forgiveness. The writers have truly challenged us to wrestle with the

question of forgiveness for war-mongers, Nazis, attention-grasping former

Kings, fair-minded Queens, and a good many

other sinners. (Perhaps we might even wrestle with the contemporary issue of forgiveness for men who sexually assault or harass women.) In his time as an evangelist, Billy Graham made it clear that

the Bible teaches that “all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God”

(Romans 3:23). Vergangenheit, the

episode, asks us significant questions about how far the forgiveness of God

could extend and leaves us wondering how we might “forgive others as God has

forgiven us” (Matthew 6:14, 15 and Matthew 18:21-35). Oh Lord, “forgive us

our sins, as we have forgiven those who sin against us.” (Matthew 6:12, New Living Translation).