While vacationing in Washington, DC this week I have been struck by the power of a great speech. Abraham Lincoln, perhaps America’s favourite President, was considered a great orator and two of his most famous speeches are inscribed on the walls of the Lincoln Memorial: The Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural Address. (While here, we have witnessed somber remembrances of the 150th anniversary of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.) The words on those walls have much to do with the freedom of enslaved people in the history of their nation and there has been more than 150 years of progress since the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1st, 1863 by that same 16th President of the United States of America. Yet, change has come slowly.

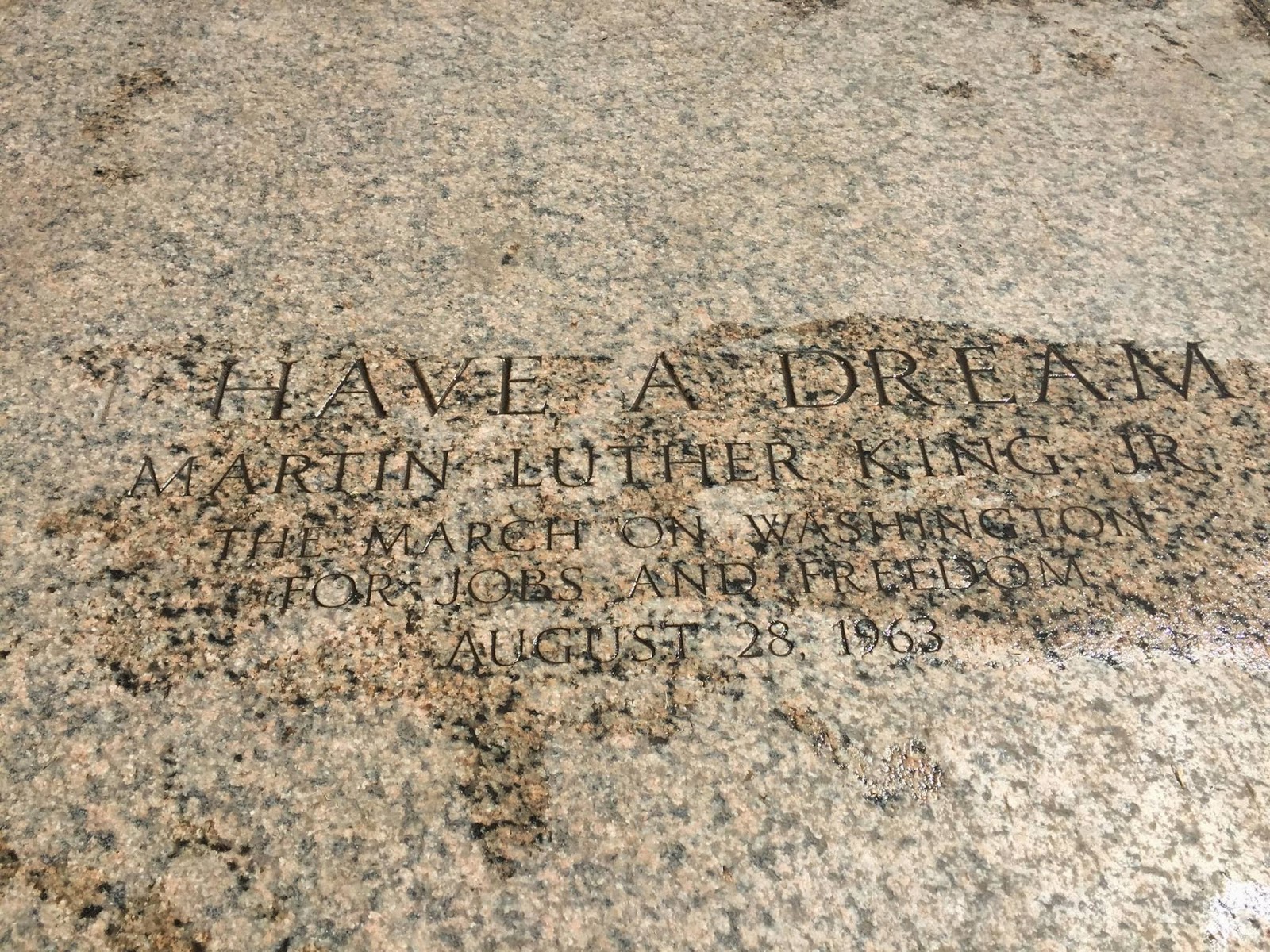

Martin Luther King Jr., 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, gave one of the greatest speeches of all time on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on August 28th, 1963. In it he pointed out that the Emancipation Proclamation “came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.” Yet, King also pointed out the great need for further progress, for he said:

One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land.

More than 50 years after Martin Luther King Jr.’s passionate speech, we find that much has changed but there is still much that needs to change. In a powerful sermon preached at Shiloh Baptist Church in Washington DC on Sunday, April 12th, Dr. Harold Dean Trulear spoke of the distance yet to go. He pointed to the disproportionate number of young black men in prison. Although blacks make up only 13% of the US population, they represent 37% of prison populations in that country. African-American males are six times more likely to be incarcerated than white males and 2.5 times more likely than Hispanic males.1

Reverend Trulear, speaking to a mostly black congregation, began with the biblical text of 1 Samuel 30:1-8 and spoke of the need to rescue their families from captivity. He punctuated the message with a call to “Go get your stuff!”2 His words inspired the people to “not be ashamed of those who are in prison but rather to visit them and welcome them back into society when they return.” The “altar call” invited those who had family members in prison to come forward for prayer; and a large crowd went forward.

As a white Canadian sitting in the Shiloh Baptist Church building that morning I knew that Canada has its own disproportions in prisons. Canada’s population is made up of approximately 4% aboriginal peoples; yet, 23% of our prison population is aboriginal.3 What sort of speech do we need that will begin to change these numbers in our own country? How might we dream of a better future? How can Canadians and Americans alike work to create a just world where all can say, “Free at last, free at last, thank God Almighty I’m free at last?”

1 U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2011, 8 tbl.8 (Dec. 2012); and http://sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/rd_ICCPR%20Race%20and%20Justice%20Shadow%20Report.pdf

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3L41NjK5gY

3 http://ca.reuters.com/article/domesticNews/idCABRE92615X20130307